“God’s will is more perfect than mine, His thoughts are purer than mine, His glory is more important than mine. He must increase and I must remember that I am nothing.”

Fra. Terrance Jean Marie

Fra. Terrance Jean Marie

Franciscan Friars of the Immaculate

“When you were younger, you used to dress yourself and go where you wanted; but when you grow old, you will stretch out your hands and someone else will lead you where you do not want to go.” John 21:18

St. John Vianney once said that, “the saints have not all started well, but they have all finished well.” He may have even said it many times because it’s worth repeating. My start in life was not as pious as his, nor was it as riotous as St. Augustine’s sounded when I read his Confessions. Growing up though, I understand both of these men had at least one thing in common: they have very special mothers. The Cure’s mother taught him while he was little to always turn his heart toward God when the church bells or the clock in their home would ring on the hour, and she died “thanking God for a son who would become a priest.” And St. Monica cried, prayed, and even shadowed her own son for many years until he finally traded in his mistress and his pride for his cross.

The patterns of life and the strongest memories usually come from childhood and from the home, and so I’ll begin my own story there. Unlike the two men above whom I admire — yet like some others — I was not graced with a God-fearing mother or with a very close family. In God’s mercy, He did not completely withdraw the gift of good sense from my mother at this early time in her life. I was baptized — perhaps at the insistence of my grandparents — at St. Julie Billiard Church in North Dartmouth, Massachusetts, on the feast of the Transfiguration in 1978, and when I was two years old or thereabouts, my mother decided to entrust me to her parents.

We lived in New Bedford, Massachusetts, in a beautiful, 1850 Victorian-style house with three floors, many wonderful rooms, a tennis court in the rear lot, four-car garage, and a dentist’s office perched on top of the garage where my grandfather worked.

I was planted in Catholic schools from kindergarten through high school, and this is where all my catechizing took place. From as far back as I can remember, I always believed there was a God, that He knew about me and watched over me in some way, and that He’d like for me to “be good.” (I understand this now as being part of the sacramental grace given to all of us at baptism.) I had no notions of rebelling against Him or my grandparents as my mother had. “Ma (my grandmother) was nice enough to take me into her house. Who am I to cause that type of trouble?” was how I thought. I never caused trouble at home — I saved it all for school, especially grammar school. High crimes were not my taste. My routine involved things like talking constantly in class, name-calling, gossip, slander, mercilessly kicking one girl in the shins every day at lunchtime, endlessly raising my hand to ask questions, blowing my nose so as to make as loud a sound as possible, eraser fights, holding grudges against deserving students and undeserving teachers — in short, nothing that caused me to be disliked, but enough for me to be seen and heard and punished. I confess that the thought of it all still makes me smile — not the mischief itself, but the general atmosphere of school. I loved grammar school. It was my home away from home, and it actually felt like a home. My teachers were like parents and my classmates were my brothers and sisters.

History class was a favorite of mine, and I think it was here that God first impressed on me the reality of mortality. I always found the years of birth and death printed after famous historical names fascinating. One of my classmates would read aloud a passage saying, “Napoleon Bonaparte (1769-1821) became Emperor of France in 1804,” and I would be asking myself what Napoleon Bonaparte might have been thinking in 1820. “I’d like to be able to go back in time and tell Napoleon, ‘You have only one year left. Better smarten up and use it wisely,’ or something like that — to get him thinking.” I reflected a bit on this not too long ago and noted how gently Our Lord had worked on me, indirectly as it were, through the mortality of historical figures. My grandfather’s death had not made such an impression. From this, and from prayers and lessons taught in school, I began infrequently raising my thoughts to God before falling asleep; if sleep came before prayer, I gave in without much fight. “I’ll make it up to You tomorrow,” I would half-heartedly whisper before closing my eyes. Only Our Lord remembers the substance and sincerity of those prayers, but the point here is that I was at least convinced of the need to pray. I was convinced of it even more when I experienced head and stomach aches. The prayers I remember most vividly — the ones I could have and would have sweat blood over — were the whole-hearted efforts petitioning God to cast some sort of spell (“since He can do all things,” I reasoned) over such-and-such a girl so that she would fall madly in love with me. It was a misuse of the gift of prayer, but at the time it seemed the best weapon since I was too gutless to ask anyone out.

A relationship with God is something like walking from the beach into the ocean. There may be holes in the analogy, but the basic idea or image seems sound to me. There are millions of people who seemingly have no desire to even visit or investigate the beach (which I’ll call “the edge of faith”): They are as Our Lord describes them in the parable of the soils. “Once life settles down, I’ll make time for God; I don’t think there’s enough scientific evidence to prove God exists; Once I experienced a personal tragedy or saw one occur, I lost all faith in God” — such are the words that fall from their mouths. My opinion on this is essentially not my own; all true opinions are not original opinions. Original opinions derive from original sin (as does all sin itself), and being fallen, I can genuinely sympathize with those who have reservations about God and His Christ. Those who refuse God lack faith simply — and I place emphasis on the word simply — because they don’t ask for it, and they don’t ask for it because having it means not having other things, namely letting go of pride, sinful choices and lifestyles, wrong notions of God, anger, resentment, fear of relationships, and even fear of rejection. It wasn’t for lack of proof or lack of knowledge that Lucifer became Satan. I say all that, but the real test comes when you arrive at the edge of faith — you must step into the water! You must begin to trust and entrust yourself to God, and for some — because of sin or because of fear and insecurity — this is possibly more frightening than Hell. My feet were in the water from childhood as it were, but it was in high school that God began pulling me farther into His ocean, and this all came about through suffering.

As I mentioned earlier, my twelve years of Catholic schooling included high school. Our Lady is the Refuge of sinners, but high school — Catholic or not — is no refuge for adolescents, especially one as insecure as I. I remember freshman year being little better (or little worse) than survival of the fittest mingled with suspicious religion classes. In the stratosphere of popularity (recognized by all as more important than sunlight, daily food, and oxygen) I was in the lower-middle class sphere, and such an unprivileged position ensured routine harassing, threats, insults, derision, etc. Acne and an unattractive smile only made the darkness around me darker. I make no claims here of resembling a persecuted angel, for I was as cold and callous toward the weak as the social elites were toward me. I only want to highlight what this misery did for me spiritually. In school, out of school, I had nowhere to turn — nowhere else to turn. My nighttime prayers intensified to the point of tears and pleas to Jesus: “Please, just have them leave me alone!” These daily humiliations and internal sufferings made me grow very dependent on Our Lord as my refuge in the night. (I see this misery as having the twofold purpose of pushing me closer to God while at the same time being a frontal assault on my pride. Jesus uses everything and wastes nothing.) There was a great release from this cruelty sophomore year, due largely — as seen through natural eyes — to me earning a starting place on our junior varsity football team, yet as I write this I’m keenly aware of the great spiritual debt I’ve racked up over these years.

I’ll end the high school chapter of my story with one other point of interest. A religious vocation was still nowhere in sight or in mind as I graduated from school, but there was a certain teacher who, with one word, convinced me that Jesus deserved and demanded more of my attention. Before one of our religion classes, this teacher was asked the following question: “Dr. Charbeneau, what are you afraid of?“ It was asked off-the-cuff, rather harmlessly, and amid some disordered teenage pre-class chatter and riot-making. I can still picture the chaos in the room. (Dr. Charbeneau was the type of devout man who was so devout that the children knew they could walk all over him.) His answer, “I’m afraid of going to Hell,” was spoken sincerely and without hesitation, and it literally froze me in my chair. It was as the guards had reported to the chief priests: “No man ever spoke like this man.” Dr. Johnson stated it in a more pointed fashion: “The prospect of death concentrates the mind wonderfully.” At ten-thirty in the morning or thereabouts, the reality of things was staring me directly in the face. There were no historical figures for me to hide behind. From this throwaway question-and-response, I began to acknowledge that God was not to be treated merely as a cosmic bell-hop. He deserved to be honored and worshipped; He deserved more of me than I had given, and more than I had been willing to give.

From 1996 to 2002, I attended a private college in Boston and studied architecture. I thought it a huge hurdle to enter college “undecided,” so I chose the architectural field on a whim. I loved Lego-building when I was younger, so I reasoned that architecture must be much the same thing on a larger scale. No one offered me any guidance, and I had little idea of what I wanted to do with my life, but nonetheless, I was confident that I could make something of myself because I loved to learn. Praise God for my love of learning, something which I lost at the beginning of high school and begged for in prayer — and received — thereafter.

City and college life presents the imagination and the senses with endless temptations, all of which had relatively little influence on me. My innocence in these things was a mixture of insecurity and a clear sense of right and wrong that my grandmother modeled. Besides, I knew I was in school to learn and study, not to disfigure my conscience. Not being overly social (one of my grandmother’s inherited dispositions), I had no interest in the party scene and, to my deep disappointment, I experienced most college social gatherings as nurturing a shallow, superficial, and even nihilistic view of life. “How meaningless it all is,” I would whisper to myself on occasion. The longer school carried on, the more frequent were such occasions. Again, my mind goes back to the scriptures: “I will take her into the desert, and there I will speak to her heart.” Behind the garnish and excitement, city life and college-age passions were a spiritual desert that pushed me toward God, further into His ocean as it were. A stone’s throw away from my apartment on St. Stephen Street was St. Anne’s Parish, which catered to college students and young professional types. It’s a literary stretch and may be somewhat out of place here, but in truth it’s accurate to note that on weekdays I walked the street of The Martyr and on Sunday I went to Grandmother’s House — or properly speaking, the House of her Grandson. I found St. Anne’s Sunday services, their singing, and the whole atmosphere of the place to be wonderful, even if, in hindsight, some liturgical activities were a bit curious. The point here is that my desire to withdraw from the world and to know more about God was growing steadily all through college.

Two other points before I move onto the final leg of my vocation story and God’s special call, the first being that one cannot draw closer to God without drawing closer to oneself — i.e., growing in self-knowledge — and feeling more tenderness toward your neighbor. The gift of loving God and the gift of loving one’s neighbor can be distinguished but they are not separate gifts, and this reality was made clear to me in college. While my desire to know and love God was growing, I was noticeably shocked when I started feeling more empathy toward my classmates who were experiencing hopelessness, disappointment, and other emotional and psychological predicaments. How do I put this into words? In simple terms, I began seeing the people around me and in front of me — my classmates, my teachers — as flesh and blood, with an immortal soul and a spirit as I had. I suspect Mother Teresa was behind some of this. I always blame the saints in these matters. A little book entitled “My Life for the Poor” came into my hands at some point, and her words left an enormous impression on me. I just now went and searched the friars’ library, and I picked up another book of hers. (It’s a book of her sayings. Like Our Lord, I don’t believe she ever wrote a book.) I open this particular book at random and find her saying this:

People are hungry for God. People are hungry for love. Are you aware of that? Do you know that? Do you see that? Do you have eyes to see? Quite often we look but we don’t see. We are all passing through this world. We need to open our eyes and see.

No ornament, no pretense; perfectly simple, and very deep — like God Himself. God cleared away some of my selfish thinking and I began to see this spiritual poverty around me. In college, it’s not usually more than one or two souls away.

The other note of importance is my discovery of Christian radio. I hesitate putting pen to paper here because I know this story is meant for Catholic eyes, but a full confession requires me to share this. In truth, when I found Christian radio I was actually searching for an old radio classics program I loved listening to as a child. The Jack Benny Show, Burns and Allen, Suspense, Lights Out Everybody, and a number of other shows would air on our local AM station before I went to bed at night, and I was hoping to rediscover some of the joy those programs brought me. One day, I switched to the same channel on the way home from work (now some ten or twelve years later) and found people talking passionately and with conviction about Jesus and His day-to-day influence in their lives. This was another great blessing. I never knew or was aware of such people, and religion wasn’t discussed on our home. I began listening regularly and took in much of the good they had to offer while ignoring the small number of anti-Catholic programs and remarks that would surface. A Catholic apologetic is not necessary here. It suffices to say that Christ prayed for His Church to be one, not many, yet among the many there are a lot of grace-filled, wonderful people who gave me a great zeal for Christ and for sharing Him with the world.

The expression “cut to the chase” seems appropriate now, and so far I’ve been giving you much chase by way of introduction to my religious calling. With God’s grace we’ve gotten this far! I’ll give as brief and honest a conclusion as my mind will allow me to give here, and I’ll ask Our Lady to make up for the rest.

It’s not unusual to find college students — especially liberal arts majors — still unsure what they want to do with their lives after graduating from college, and still unsure about life in general. They become like lost fish in a sea of debt, and the curious solution for many is to head off to graduate school. Perhaps there’s a fear of becoming an adult behind it as well. By the time I graduated in 2002, I was happy to finally be an adult (in my own eyes) but I was decidedly uninterested in architecture. “There’s too much suffering in the world, too many empty lives, too much good that needs to be done.” I wasn’t sure what I was aiming at with this type of thinking, but it couldn’t be done in an architect’s office. Mother Teresa had convinced me that when you don’t know where to be, it’s best to be with the poor, and so I arranged to spend a come-and-see week at a volunteer shelter in Arizona run by the Holy Cross fathers. I’m just remembering now that this all came about through St. Anne’s Church! They arranged an evening where speakers came and spoke to our parish about volunteering for a year after college graduation. The speakers were three college-age girls, and they spoke to an audience of two, not counting St. Anne’s staff, which made the gathering seem more impressive. Being one of the two who attended, I left that night convinced that God would be happy if I offered a year of service to Him and His poor.

My week with the volunteers and the Holy Cross fathers opened my eyes to the everyday life of priests. “How great is the priest! The priest will only be understood in heaven. Were he to be understood on earth, people would die, not of fear, but of love.” I borrow that from St. John Vianney, and it pretty well fits my view of the priests I spent time with in Arizona; not that they seemed overtly holy (Our Lord has more inside knowledge on that than I do), but just their presence, being with them, seeing them work and interact with the guests and the volunteers — all of it inspired me. The work itself was a bit difficult, but joyous. I was offered a return visit only for the summer season for reasons I was unaware of, and I declined because I wanted the guarantee of a whole year. In spite of my disappointment, which was great, I experienced a surge of confidence in God. In Phoenix, I had told Him that I would do whatever He asked, no strings attached. (It was the first time I hadn’t added strings.) “What is is that You’d like me to do?” I asked while I was driving home one day, and it was then that I remembered the priests. Very quickly — perhaps impulsively — I told Him that I wouldn’t mind being a priest. I remember the incident vividly, though there’s not much detail to add. It’s a little like C.S. Lewis’ conversion experience, where he was a passenger on a motorcycle ride who, when he started the trip, didn’t believe that Jesus Christ was the Son of God, and by the time he arrived at wherever he was going, he did.

My desire to be a priest has grown steadily since 2002, though my expectations have expanded to include “whatever the will of God is,” and my prayers are and continue to be that God will purify, humble, and perfect me. God’s will is more perfect than mine, His thoughts are purer than mine, His glory is more important than mine. He must increase and I must remember that I am nothing. I desire not my own glory because it’s an empty desire. Turn on the television if you need further convincing of how empty is the glory that we give to each other.

In regards to my search for a religious order, I began rather naively, as I had with picking colleges. I had heard some vagaries about certain orders undermining the mission and teachings of the Church, but such ideas seemed absurd to me, like sawing off a tree branch that one is sitting on. “I’ll join an order whose charism and mission appeal to me, and God will do the rest,” was my guiding thought, though I also had a strong desire to live poorly as Our Lord lived. Choosing to be poor for Christ gives freedom to the heart, and I found that material possessions possessed me, my thoughts, and my heart more than I possessed them. The possession was subtle but real. Material wealth is only good if you do a lot of good with it, and even then it’s still dangerous to the soul.

Diocesan priesthood had little attraction to me. The idea of being a local priest appealed to me because I knew that every street and town is God’s vineyard, but I found most local priests uninspiring. I say this without wishing to be disrespectful. Most diocesan priests whom I knew or at least was familiar with were kind men, but, to me, uninspiring as clergy. “I want vocations, not numbers,” Mother Teresa would say, and I feared that if I became a diocesan priest, I might turn into a number through poor formation. As the clergy and religious go, so go the faithful. This is proven historically since all heresies have come from the clergy, not the laity; hence my fear of being poorly formed as a clergy/religious. I decided I would be a missionary: Mother Teresa would approve. (It’s obvious that I have a great love for her. In spite of the affection, I’ve never felt a pull to join her order as an MC brother.) Because of their reputation as scholars and as “the marines of the Church,” and because they had access to so many young minds and hearts hungry for truth and for God, I chose to apply to and enter the Jesuit order. Shortly thereafter I learned that this choice was not a healthy alternative to diocesan priesthood. Five months after entering the Jesuits’ novitiate, I was told by my superior that he thought it was not my calling to be a Jesuit, and after a day and night of reflection, I agreed and we parted ways within a week. An old saying goes that there’s no use throwing mud at others because your hands get dirty and you lose a lot of ground, so I won’t speak much of my time with the Jesuits other than to say that it was a great internal cross. Many of the men I was with were genuine and well-intentioned, and some were like brothers to me, but there were others busy sawing off the branches they were sitting on. The Society itself was very gracious toward me, and I have no grudges and very little regrets, but I did leave quite shaken about my prospects as a religious.

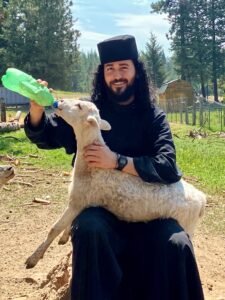

So as the whale dealt with Jonah, God spit me out of the Jesuits and I landed at the doorstep of the Franciscan Friars of the Immaculate in downtown New Bedford. God has His ways. If I could turn into a leaf and have Him blow me about as He wills, I would be very happy. Such is the way of the cross and the way of the saints, and praise God you can’t fit much self-love into a leaf. I’ve spent a good deal of time with these friars. They fashion themselves as Marian defenders, knights of the Immaculate, and as best as I can gauge, their life suits me. Our Lady never tires of more children or more soldiers. St. Maximilian Kolbe is the inspiration for their spirituality and their media apostolate, which includes websites, writing and publishing books, audio CDs, all for the triumph of the Immaculate Heart. God graces each friar with special gifts and abilities, the friars give all they receive to Our Lady, and she lays everything before the feet of her Son. All gifts return to their source, sanctified by the new Eve. That’s my own condensed and incomplete understanding. The friars have already made a significant impression on my life. The lay people alone under their care have taught me more about Divine Providence and humility than anything I’ve seen or read.

This seems as good a place as any to end, and I’ll end with a short lesson on history, still my favorite subject. The 20th century was the century of militant atheism: Marx, Freud, Darwin, Hitler, Lenin, Stalin, Mao, Pol Pot, Communism, Secularism. Conservatively, over 100 million were murdered under atheistic regimes in the last century. By most accounts, that’s more bloodshed than the previous nineteen centuries combined. I have a strong intuition that this century will be either one of two things, or both: either it will be a Catholic/Christian renaissance by way of the Americas, Africa, and China (possibly Russia), or it will be the Muslim century, or both. Secularism is not a life-giving or life-affirming philosophy, and so it cannot endure. However it pans out, we each have a role to play. Our Lady will be very busy during this century, more so than ever. It’s my intention to work with her and for her for the triumph of the Church at whatever personal cost, and the most precious cost is always our own self-will. “Thy will, not my will, be done.” Our Lord and Our Lady will do many wonderful things through us if we entrust everything to them, so don’t be afraid. Don’t fret over your sins, your weaknesses, faults, insecurities, fears — don’t be anxious about your life. Don’t be lukewarm. God has chosen us. He is Ours and we are His. Let Him complete the good work He has begun in you, and as He does with all His saints, He will help you to finish well.